The matrix supporting life

From cells to tissues

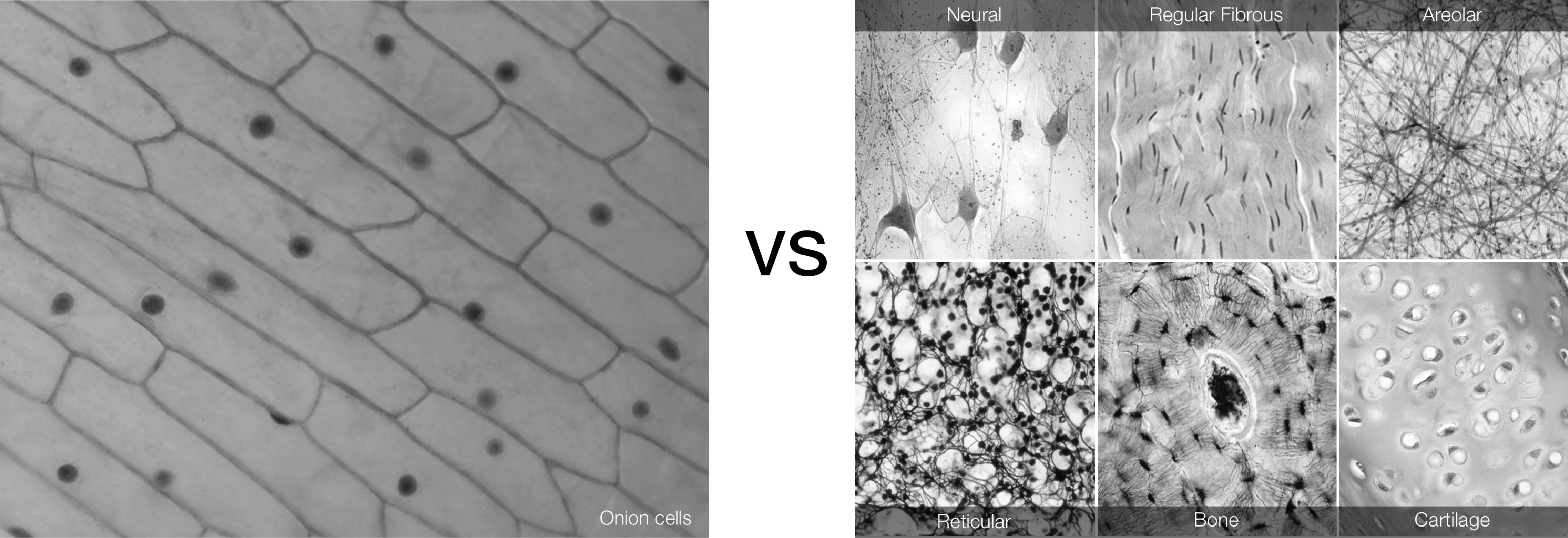

During biology classes in high school most of the students get the chance to see the structure of onion tissue. The way that onion cells are connect to each other might lead to the wrong idea of how tissues are organised. Our body is made of different tissues, with different properties.

A bone cell is different from a brain cell. Different cells form different tissues. However, not only cells are responsible for differences between tissues. Living tissues are more than packed cells.

Like the cement that keeps bricks in a wall, cells use a complex meshwork of sugars, water, minerals and proteins to hold together as a tissue. This mixture fills up the space in-between the cells and is therefore designated by extracellular matrix (ECM). Besides providing a structure support to the cells, the ECM plays a crucial role in several cellular processes, such as cell survival, development, adhesion and differentiation of stem cells.

Matrix and tissue engineering

Found in multicellular organisms, stem cells are cells with the potential to develop into different cells lines. They are unique as they are able to self-renew through cell division or become tissue- or organ-specific cells (under certain physiologic or experimental conditions). While crucial during embryonic development, stem cells are also important at a later stage, where they serve as an internal repair system, dividing essentially without limit to replenish other cells as long as the person or animal is alive. When a stem cell divides, each new cell has the potential to either remain a stem cell or become another type of cell with a more specialized function, such as a muscle, a bone or a brain cell. As a consequence, stem cells hold great potential as a cell source for regenerative medicine. When a stem cell divide, it chooses to keep its pluripotency (i.e., the ability to become any type of cell) or it becomes a tissue specific cell, it ‘differentiates’. It is known that the properties from the ECM guide the differentiation process. For instance, if surrounded by a hard material, stem cells will become bone cells while if the material is soft, they will be transformed in brain cells. However, this phenomenon is still not well understood. In this project I will develop new chemical and biological tools to study how cells sense and react to the physical forces and properties of the ECM. We are using synthetic materials that mimic the natural cellular environment and label proteins involved in force-sensing mechanisms. By combining these materials and probes with advance microscopic methods, we will be able to ‘see’ how the matrix controls cellular behavior, at a molecular scale. The knowledge of how forces control the fate of stem cells will have immediate application on both stem cell therapy and tissue engineering fields.

Matrix and cancer

Medical doctors often diagnose tumors based on differences in tissue rigidity sensed by palpation. Specialized researchers know that cancer involves changes in the mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) - the complex meshwork that fills up the space in-between cells. There is a growing consensus that these changes are not merely a consequence of cancer progression but could also play an important role in its evolution. However, a detailed understanding of how external forces influence cancer progression is still missing. One of the hallmarks of cancer is the invasion into new tissues, i.e., when some pioneer mutant cells leave the tumor mass and start new colonies in other areas of the body. These distant settlements of cancer cells are named metastases and cause the majority of cancer related deaths. The involvement of ECM and cancer associated cells in metastasis is only now surfacing, with accumulating evidence of the crucial role of biomechanics in this process. Part of our research is focused on using new biomimetic polymers and state-of- the- art microscopic methods to study the interplay between the mechanical properties of the ECM and behavior of cancer cells. A deep comprehension of how physical forces affect the tumor microenvironment will help scientists to develop novel diagnostic and therapeutic tools for early detection and delayed cancer progression.